In Japan, one well-known and effective method for learning English is by watching Disney movies. I myself have been using this method for a long time. From an outsider’s perspective, it’s hard to tell whether you’re actually studying English or simply enjoying a movie — which made it a perfect excuse to silence my mother, who used to constantly nag me to study when I was younger.

But in truth, this method was quite effective. By subconsciously absorbing the rhythm of English sounds and the way things are perceived in English, I found that my reading speed on English exams improved dramatically. More importantly, I started getting the kind of questions right where I couldn’t logically explain the answer, but somehow just knew it was correct.

Now, if we apply this approach to the (relatively few) learners of Japanese, watching anime in Japanese could be a similarly useful study method for them. However — and this is where the real issue begins — anyone trying to learn a language through a movie or show faces a huge barrier. That is, simply breaking down sentences into individual words and looking them up in a dictionary won’t allow you to grasp the sentence structures and patterns that native speakers naturally use in everyday conversation.

Dictionaries often list multiple meanings for a single word, making it difficult to tell which one applies in a given situation. And even if you manage to figure that out, it’s still hard to understand how the word functions within the flow of the sentence. In the end, many unresolved questions pile up, leaving learners frustrated and forcing them to memorize things without fully understanding them. I believe this is the main reason people give up on this kind of study method.

So this time, as an experimental idea to perhaps help out some of those frustrated Japanese learners, I’d like to post an article where I thoroughly explain the Japanese grammar used in anime scenes. If there’s a particular scene from an anime you’ve watched where you’d like to see a similar breakdown and explanation, please feel free to let me know. If I continue this series, I’d be happy to cover those scenes as well.

This time, I’ll be introducing a Japanese short animation called "Milky☆Subway."

The story is set in a world where an extensive transportation network stretches across the galaxy. Two main characters, having committed traffic violations, are ordered by the police to perform community service — cleaning the interior of an interplanetary train. While carrying out this task, they unexpectedly find themselves caught up in a major incident.

The scene I’ll be focusing on features a female police officer explaining the details of this community service assignment. In the scene, six characters — all traffic violators — take turns asking her questions about it.

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/Wb71kN0hOZg?feature=share

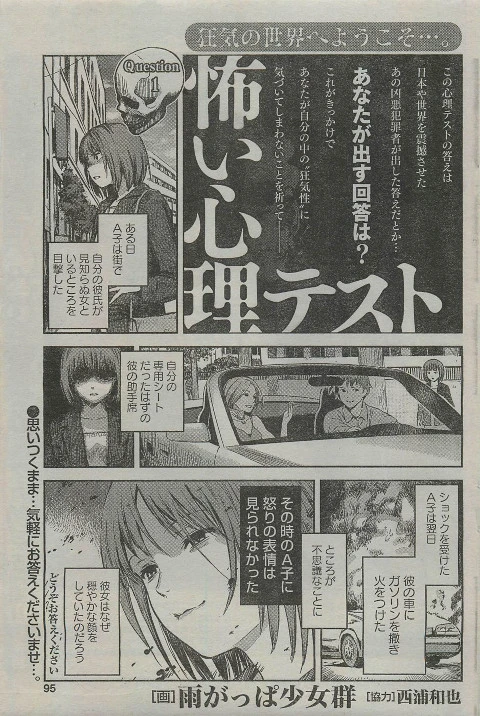

他質問(hoka shitsumon): Any other questions?

はい(hai): Over here.

もぉなに(mo-o nani):What is it?

具体的に『奉仕活動』って何するんすか?(gutai teki ni 'houshi katsudou' tte nani suru-n su ka?):What exactly are we doing for this "community service"?

だぁか……それはフツーに良い質問だ(daka... sore wa futsū ni ii shitsumon da): I'll have you-- Oh, that's actually a pretty valid quesiton.

他質問(hoka shitsumon; Any other questions?)

[Words]

・他(hoka):other, the rest

・質問(shitsumon):a question

In this scene, as you can see, the character speaks in a rather blunt, curt manner. She tries to complete her sentence using the absolute minimum of two words: "他 (hoka; other)" and "質問 (shitsumon; question)."

For native Japanese speakers, this expression isn’t unnatural, but it does sound quite abrupt and unrefined. It lacks the softening phrases or grammatical structures usually added to make a question sound polite or neutral. It’s the kind of phrasing you might hear from a stern police officer, military personnel, or someone intentionally keeping their tone short and business-like.

はい(hai; Over here.)

[Words]

・はい(hai):yes, okay, (perdon?, now!, over here)

In Japanese, "はい (hai)" is most commonly used to mean "yes" (by the way, its opposite "no" is "いいえ (iie)").

However, it also functions as a filler word — a word inserted between phrases that doesn’t necessarily carry meaning on its own ("uh", "I mean", "you know", ...). And in other cases, like the one in this scene, it’s used to signal that the speaker is about to say something or take their turn in the conversation.

I once read a Japanese linguistics paper claiming that the true function of “はい (hai)” is to declare to your conversation partner that "I am accessing the memory in my brain relevant to the topic we’re discussing." While that’s an interesting theory, honestly, you don’t need to overthink it. It’s much easier to just learn the different uses of “はい (hai)” through real-life examples, case by case.

もぉ、何!?(mo-o nani; What is it?)

[Words]

・もぉ(mō):(colloquial, interjection) used to express frustration

・何(nani):what

The word "もぉ (mō)" is an interjection that expresses frustration or irritation. Depending on the situation and the speaker’s personal style, it can also appear as "もー (mō)" or "もう (mō)" in writing. However, since the pronunciation is usually about the same, it’s relatively easy to recognize in spoken Japanese.

In this scene as well, you can clearly see that the character is visibly frustrated at having received yet another question.

The following word "何 (nani)" simply means "what." In this case, while the literal translation would be "What?", the translator chose to render it as "What is it?" in English to better reflect the tone and nuance of the scene. This is a good example of how translators often prioritize context and naturalness over strict word-for-word accuracy.

具体的に『奉仕活動』って何するんすか?(gutaiteki ni ' hōshikatsudō ' tte nani suru-n suka?; What exactly are we doing for this "community service"?)

[Words]

・具体的(gutai + teki):(adverbial)concrete, specific

・に:(adverbializer particle)

・奉仕活動(hōshi + katsudō):service + activity

・って(tte): colloquial form of "とは" that indicates that a word or a phrase is to be defined or explained

・何(nani):what

・する(suru):do

・ん(-n):colloquial transformation of の(particle of emphasis)

・す(su):contration of です(verb that makes polite form)

・か(ka):interrogative or rhetorical question particle, similar to a question mark ("?").

This line is a bit long and involves several layered colloquial expressions, so let’s unpack it carefully.

The first phrase, "具体的に (gutaiteki ni)", is the result of a two-step transformation. To begin with, there is the noun "具体 (gutai)", which means "something concrete." (In philosophy, this noun form occasionally appears as the antonym of "抽象 (chūshō; something abstract)", though it’s not a particularly common word in everyday vocabulary.) Then, by attaching "的 (teki)", which functions like -like(ly) or -ish(y), the word shifts into an undifferentiated state between an adjective and an adverb. Finally, when the adverbializer particle "に (ni)" is added, the word is firmly established as an adverb.

If we summarize this progression, "具体的に (gutaiteki ni)" can be translated as "specifically."

Incidentally, when the adjectivizer particle "な (na)" is attached instead, as in "具体的な (gutaiteki na)", it forms an adjective meaning "specific."

"奉仕活動 (hōshikatsudō)" is a compound word combining "奉仕 (hōshi)," meaning service (often in a religious or social context), and "活動 (katsudō)," which cleanly translates to "activity". In fact, the usage of "活動 (katsudō)" matches "activity" so neatly that one might guess it was coined in the Meiji era to translate the English term — though that would need verification.

So "奉仕活動 (hōshikatsudō)" literally means "service activity," but the translator chose "community service," a phrase that better fits the legal and disciplinary context in which the characters find themselves in this scene — having committed a crime and being sentenced to some form of public service as punishment.

"って (tte)" is the casual spoken form of "とは (towa)," a particle used to mark a word or phrase for definition or explanation. Wiktionary even lists its function as "indicates that a word or a phrase is to be defined or explained." In practice though, you’ll overwhelmingly encounter this in the form "Xって何 (X tte nani)" meaning "What is X?" It’s a good idea to remember this as a set phrase for everyday conversation.

"するんすか? (surun suka?)" is where things get colloquial and a little complex:

・"する (suru)" means to do.

・"ん (-n)" is the casual spoken form of の (no), a particle used to add emphasis or explanation.

・"す (su)" is a casual contraction of です (desu), the polite copula often used by younger male characters or 'informal respectful' speech.

・"か (ka)" is a particle that turns the sentence into a question, much like a question mark "?".

So when combined, "何するんすか? (nani surun suka?)" can be parsed as a casual but slightly polite way for a younger character to ask a superior or authority figure "What exactly (are you/are we/am I...) (supposed to be) doing?”

Now that we’ve developed a deeper understanding of each individual part, let’s move on to learning how these parts are combined. The reason is that this sentence, grammatically speaking, isn’t quite correct — and even if you grasp the meaning of each individual piece, it’s still difficult to work out how they’re meant to fit together.

具体的に(gutai teki ni; spesifically)

『奉仕活動』 (hōshikatsudō; service activity)

って何するんすか(what ... doing)?

Strictly speaking, this sentence actually needs to be divided into two separate parts:

"『奉仕活動』って何 (What is 'service activity'?)" and "何するんすか? (What [are we] doing?)"

The young man in this scene tends to use extremely casual, broken expressions. As a result, he unconsciously (and a bit forcefully) fuses two otherwise unrelated sentences together by using "何 (nani; what)" as a kind of linguistic glue. In formal Japanese, this wouldn’t be a grammatically correct sentence — but even so, native speakers of Japanese would understand what he’s trying to say, albeit with a slight sense of awkwardness.

Essentially, he means something like:

"What is this 'service activity,' and what (are we supposed to be) doing (for it)?"

When this sense is translated into natural English, the best rendering would be:

"what exactly are we supposed to do for this 'service activity'?"

Finally, regarding "具体的に (gutaiteki ni; specifically)" — its placement in a sentence is relatively flexible and can shift depending on the situation or what nuance the speaker wants to convey.

For example:

- Placing it at the start like this young man does, "'具体的に'、奉仕活動って何するんすか?" (Specifically, what are we doing for this 'service activity'?), suggests that the first thing on his mind is the desire for concrete examples.

- Saying "奉仕活動って、'具体的に' 何するんすか?" would feel, to me, like the most natural and neutral phrasing.

- Ending with it, "奉仕活動って何するんすか?'具体的に'。" has a kind of pressure to it — as if he’s saying to the police officer “I’m begging you, give me something concrete here.” I personally like this one too.

だぁか……それはフツーに良い質問だ(daka... sore wa futsū ni ii shitsumon da; I'll have you-- Oh, that's actually a pretty valid quesiton.)

[words]

だぁか:An interrupted phrase, almost saying "だから (dakara; I said)," but cut off

それ(sore):it

は(wa):(particle marking the topic)

フツー(futsū):eye dialect of 普通 meaning "normal" or "natural"

に(ni):(adverbializer particle)

良い(ii):good

質問(shitsumon):question

だ(da):(colloquial copula)to be

The word "だから (dakara)" usually translates to the colloquial "therefore." But in this scene, it doesn't function as a logical connector. Instead, it's better understood as a frustrated interjection—something akin to "didn't I say it?", expressing irritation at having to repeat oneself. Why "だから (dakara)" can take on this nuance is honestly a bit of a mystery, even to me as a native Japanese speaker.

The phrase “それはXだ (sore wa X da)” can be translated straightforwardly as "It is X."

Here, "それ (sore; it)" is the subject, and "だ (da)” is the copula or “to be” verb, appearing at the end of the sentence. This ordering reflects the typical SOV (subject–object–verb) sentence structure of Japanese, as opposed to English's SVO (subject–verb–object). You can see a glimpse of that word order at play here.

Incidentally, the polite form of "だ (da)" is “です (desu),” which is overwhelmingly used in formal or first-time encounters. You might have noticed that Japanese speakers often say “desu” a lot—even if you don’t speak the language yourself. However, in this particular scene, the female officer is displaying a rather confrontational attitude toward someone breaking the law. Her speech is accordingly rough, and she uses the blunt "だ (da)" instead.

As for "フツー (futsū)," this is a stylized spelling of "普通 (futsū; normal/natural)" using katakana (カタカナ) instead of the standard kanji (漢字) or hiragana (ひらがな). This usage can be seen as a Japanese equivalent of 'eye dialect' in English—where phonetic or nonstandard spellings are used to convey casualness, accent, or personality. If you’re unfamiliar with the term eye dialect, examples in English include writing "women" as "wimmin" or "school" as "scool." The pronunciation doesn’t change, but the altered spelling conveys an informal or idiosyncratic tone. Given this officer’s personality, it feels entirely natural that she would use this kind of expressive language.

And here again we see the particle "に (ni)," which in this case serves as an 'adverbializer.' This makes “普通に (futsū ni)” mean something like “normally” or “naturally.” Interestingly, in the English subtitles, it was translated as “actually,” which feels like a slightly acrobatic (yet contextually clever) choice.

Finally, “良い (ii; good)” + “質問 (shitsumon; question)” simply translates to “good question.” No further explanation is really needed there.

Now then, just like before, let’s take a look at how the sentence is constructed.

だぁか…… (daka... ; I'll have to--)

それは (sore wa; that's)

フツーに良い質問 (futsū ni ii shitsumon; actually a pretty valid question)

だ(da; -)

As we discussed earlier, Japanese sentences follow an SOV (subject–object–verb) word order, which means that verbs are typically placed at the end of the sentence. In this case, the "V" is a copula, so it may be more accurate to describe the structure not as "SOV" but as SCV, where "C" stands for "subject complement." Here, that complement is "質問 (shitsumon; question)."

In Japanese, modifiers that describe the complement typically come before the noun they modify. That’s why the phrase becomes "フツーに良い質問 (futsū ni ii shitsumon)"—literally, "normally good question," or more naturally, "actually a good question."

Taking all of that into account, the full sentence might best be rendered in English as:

"I’ll have you—Oh, that’s actually a pretty valid question."

Finally, here is the original Japanese dialogue with no annotations or explanations:

Officer: 「他質問」

Man: 「はい」

Officer: 「もぉなに」

Man: 「具体的に『奉仕活動』って何するんすか?」

Officer: 「だぁか……それはフツーに良い質問だ」

This passage is something I definitely want to include when discussing this topic. Please feel free to use it according to your own level of Japanese learning. For example:

- If you can read along while listening to the audio, that’s OK.

- If you can pronounce the lines correctly, that’s OK.

- If you understand the meaning, even better.

- And if you can memorize the whole passage and recite it at the same speed as the anime, that’s excellent.

That brings us to the end of this article. Thank you very much for reading all the way through.

At the beginning, I mentioned that this kind of detailed explanation was something I personally wished someone had done for me back when I was studying English. But as you can probably tell from this article, breaking down every single line of dialogue like this is a tedious and time-consuming task — and I realize now that it was a rather selfish wish on my part. It’s the kind of thing you wouldn’t feel motivated to do unless someone specifically asked you for it.

That said, I was fortunate that the users on Newgrounds were kind and supportive. Whenever I posted a question or sent a private message, people would take the time to reply politely and helpfully, and in their own way, they became part of my learning process. I’m genuinely grateful to those who helped me with English back then.

So if you’re a Japanese learner and ever find yourself wondering, “Why is this particular phrase being used in this situation?” — please don’t hesitate to ask. As a native speaker, I can almost certainly explain it for you. In fact, I’d be happy to turn your question into the topic of a future article.

And lastly, the anime we looked at in this article—“Galaxy Express Milky☆Subway”—currently has two episodes available on YouTube, with subtitles in 11 languages. If this caught your interest, I highly recommend checking out the channel! Personally, I absolutely love the character designs and personalities—every single one of them is super cute!

P.S.

On a different note, there’s something I’ve been wanting to ask about English as well.

In the past, I used to deal with NSFW content, and because of that, I’ve been interested in finding words that were once considered normal, everyday vocabulary — but gradually became associated with euphemisms in NSFW works, to the point where people now avoid using them in casual conversation.

In Japanese, a famous example would be "お兄ちゃん (onii-chan; meaning big brother)." It used to be a common, innocent way to address one’s older brother, but over time, it became heavily associated with works that imply "dangerous" relationships. As a result, it’s no longer something you’d casually say in everyday conversation.

I’m sure English must have words like this as well, but it’s been difficult to find anyone willing to explain them to me. I sometimes feel a bit lonely about it. If you happen to know of any examples — whether in English or in your own native language — I’d be really interested in hearing about them.